How do we make sense?

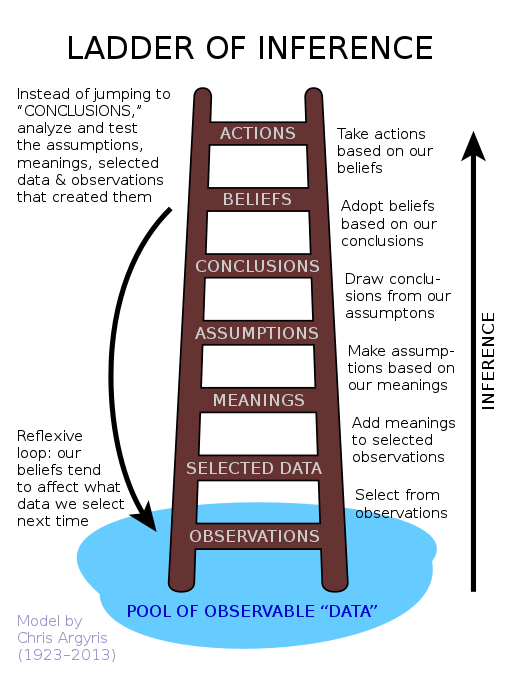

Researchers and scholars have been trying to understand how we make sense of our experiences for ages. Chris Argyris and Donald Schoen created the ladder of inference model to describe human decision-making. This model shows how we become consciously aware of available data and attribute meaning to that data, ultimately influencing our actions. For example, let’s say you observe the weather widget on your phone, which indicates that the outdoor temperature is 100 degrees Fahrenheit. You might interpret this data as meaning that it is very warm outside. As you continue to climb the ladder of inference with this now meaningful data, you may conclude that it is too hot to go outside because you believe it will make you very uncomfortable. Since feeling uncomfortably hot is undesirable and being in a cooler temperature is more pleasurable, you decide to stay inside. This process occurs frequently throughout our days. We need to recognize that we have the ability to consciously choose to reassess our subjective interpretation and meaning of the data as we go up or down the rungs of the ladder. For instance, if we were in the Mojave Desert where temperatures regularly exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit, then 100 degrees may seem comparatively more inviting for outdoor activities.

What is a ladder of inference made of?

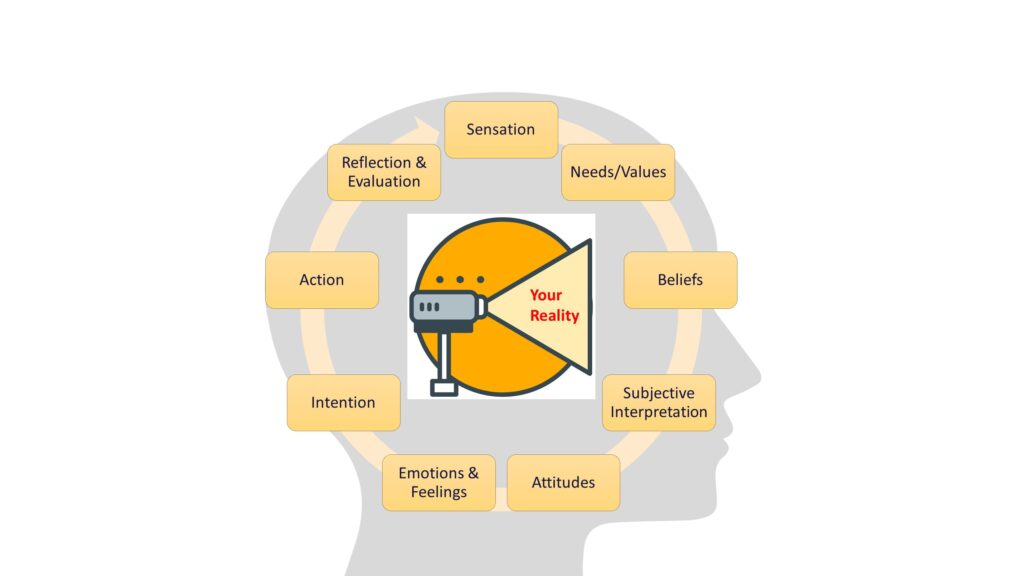

Our values form the rungs of our inference ladder. They influence our selective perceptions, judgments, attention, emotions, and actions. Based on the studies of Prof. Steven Reiss, Ph.D., there are sixteen basic human needs that we all naturally value. However, what sets us apart as individuals is the way we prioritize these needs and the quantity necessary to achieve temporary satisfaction. Our values play a crucial role in our conscious awareness.

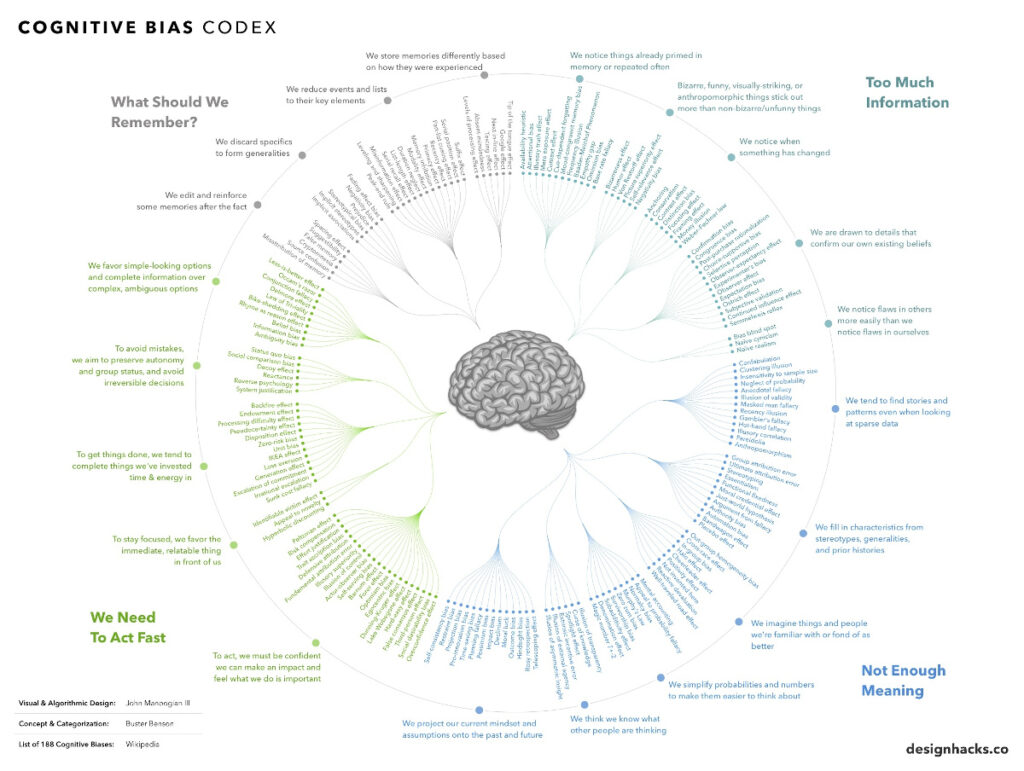

We naturally are consciously aware of what we value or what matters most to us personally. We tend to ignore things we do not value. So, if we look at the data pool our ladder of inference rises out of, we are much more likely to focus on data that aligns with our values and ignore conflicting data. Some refer to this natural tendency as a preference or bias. But, as you will see from this brilliant infographic below from visualcapitalist.com, we have many built-in biases that influence our sense making processes and memories.

Advocates of the ladder of influence advise to try to never climb any higher than you must to form an appropriate response. The higher we mentally climb up the ladder, the more removed we become from the actual data.

Testing our inferences

Consultant Richard Schwarz offered a simple series of questions that we can use to test the validity of our inferences.

- What data am I considering and not considering?

- What is the simplest and most generous way to explain this data?

- What are the likely consequences if I act on my inference as if it is true? What are the likely conequences if I act on my inference as if it is false?

- How can I test the validity of my inference?

- What is a wise response to my inference?

- Now, the biggest question: What about this data matters most to me? This step asks you to consider your values.

We often use our inferences to tell us a story that we believe is true to explain or make sense of whatever we are thinking about or experiencing. Using the ladder model can help us to consider the possibility that there are other possible explanations for the data or that our story is incomplete or wrong.

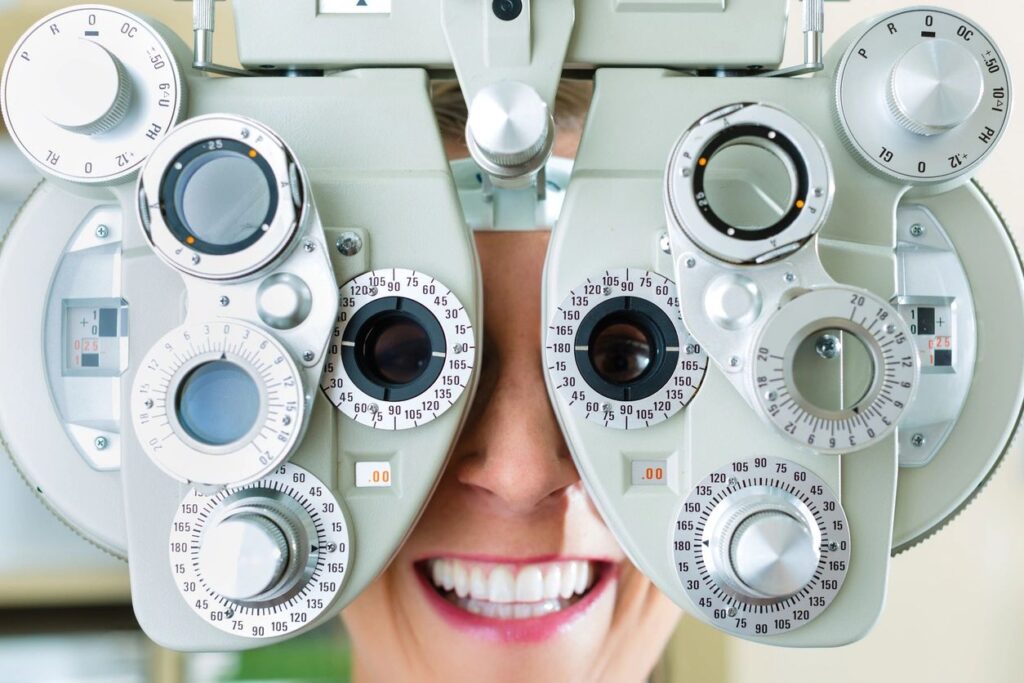

We forget we wear glasses

We view everything we see and think through the lens of our values. We use our values so instantaneously that we often are unaware that we are making value judgments. It’s like we forget we are wearing our sunglasses indoors until we finally realize the room is darker than it should be. Our values are our primary filter to sort out what data we notice and what we ignore. This is why our values are our foundational framework used to create the ladder of inference.

What matters to me?

We naturally know what matters most to us based on our values, but we may not be able to rationally prioritize our values. We also may find it difficult to communicate our values to other people, especially if they have opposite values. Professor Reiss addressed this issue by creating the Reiss Motivation Profile®. This tool measures how you prioritize the sixteen basic human values and how intensely you experience these values compared to other people. Armed with this critical values data, you can better understand how you choose the data you notice and how your values influence your judgment at each rung of the ladder of inference. The data represents what information is available to consider, and your values predict why you will be motivated to notice some data and ignore other data.

Everyone uses a different ladder

Everyone uses a different ladder of inference created out of their values system. This is why we each have different perspectives, inferences, opinions, and conclusions. Ignorance of the fact that we each experience a different subjective version of reality in near real-time causes frustration, interpersonal conflicts, and reduces the effectiveness of collaboration.

Dialogue is our most effective means of understanding another person’s ladder and explaining our own. We cannot assume our inference is the only possible explanation for the data we encounter. The view is likely very different a few rungs up on someone else’s ladder of inference. Multiple perspectives can conflict and yet all be true or at least believable. It is unwise to believe one person’s viewpoint is the only way to make sense of the true story. Before you try to collaborate, talk about each other’s values and then invite everyone to use their ladders to share their version of the story that makes sense to them.

Views: 107